In the 1700s, if you wanted a portrait of yourself or a family member, you had to sit for hours in a studio where an artist would painstakingly create a likeness of your image using canvas, brushes, and oil paints.

But in 1816, a new technology was invented called the camera. Suddenly, you could get a much more accurate portrait of your family in far less time.

But there was significant skepticism about the camera from traditional artists. Many portrait painters feared that the camera would render their skills obsolete. The idea that a machine could replicate what artists had spent years perfecting was unsettling. Critics argued that photography lacked the soul, creativity, and interpretive qualities of hand-rendered art.

Some viewed photography as a mechanical, soulless process rather than a legitimate art form. The camera’s ability to capture reality with such precision was seen as “too easy,” and skeptics believed it removed the human touch and imagination that defined true art.

As cameras became more portable, people grew concerned about privacy violations, fearing that photographers could capture their likeness without permission. Some even believed that taking a photograph could steal part of a person’s soul, an idea that persists to this day in parts of the world.

Photography sparked debates about what constituted “real art.” Artists and critics feared that photography would undermine the value of traditional artistic skills, such as drawing and painting. Some worried that it would devalue the concept of art altogether.

In some cases, photography was met with religious opposition. People worried about the morality of “freezing time” or capturing the divine beauty of God’s creation in a mechanical way.

While some portrait painters may have lost work at the time, many adapted and began to incorporate photography into their work. Now, over 200 years later, photography is accepted as both an art form and a technical skill. Ultimately, photography didn’t replace traditional art; it expanded the boundaries of what art could be.

Why are we talking about photography?

Because for Christian authors, there’s a similar debate about an elephant in the room that we have NEVER talked about on the Christian Publishing Show before.

The elephant is AI.

AI is not going away. Neither Congress nor the courts will ban it. The copyright office can’t ban it either. Technology is always changing, and we can choose to push back or adapt and use the tools to our advantage.

So, how can Christian authors use AI tools in ethical ways?

I asked Kate Angelo. She’s a Publishers Weekly Bestselling author, Selah Award Winner, and she serves on the executive board of ACFW.

Is it a sin to use AI?

Kate: Isn’t this a gray area for so many people? Many writers are motivated by doing what’s morally right, and they’re the ones who are unsure whether using AI is a good or ethical thing to do.

Do you remember when Photoshop became controversial? Everyone was using Photoshop, and people started saying, “We’re not going to be able to tell what’s real anymore.” It was the photographers, who were already using cameras, who gave Photoshop users a hard time. Now everybody uses it.

Thomas: The tables have turned. Photoshop, and the way it was used, was a lot like painting, only with digital brushes. Now, photographers feel threatened by the rise of digital “painters.”

Kate: That same threat is back. People are saying, “Why hire a graphic designer when you can have AI do it?” But again, it’s going to be a tool.

I think authors will actually be some of the best at making graphics, because we use words to help people visualize what we mean. Now we can use those same words to help AI visualize what we want to see in a graphic. From there, we can get closer to what we’re actually looking for.

Is technology good or evil?

Thomas: People wonder whether technology can be good or evil.

If you go back 100 or 150 years, there were famines all over the world. The total number of calories produced globally wasn’t enough to feed everyone. The demand for food exceeded supply.

One problem was that the soil wasn’t very fertile. One of the key missing nutrients was nitrogen. Even though there’s nitrogen in the air, it’s different from nitrogen in the soil. It has to be converted into a solid form that plants can absorb. Some plants do this naturally, but we didn’t have a process for doing it at scale.

So along came Fritz Haber, who invented the Haber-Bosch process, which trapped nitrogen from the air into a solid form that could be added to soil. That was the beginning of what’s known as the Green Revolution, where farming productivity skyrocketed. Today, the world’s farmers produce far more food than we need. We’ve gone from a world plagued by starvation to one where obesity is a bigger concern.

You’d think Fritz Haber would be seen as one of history’s great heroes. He saved literally billions of lives by making it possible to feed the world.

But he also used that same chemical process to invent chemical warfare. He’s the father of mustard gas, used in World War I. So the same scientific breakthrough that did incredible good was also used for great evil. And it wasn’t just “scientists in general.” It was the same guy.

That’s why Fritz Haber is remembered not as a hero, but as the archetype of the evil scientist. Every Bond villain with a German accent is based on Haber. Even though he saved billions of lives by revolutionizing farming, he’s remembered as the evil inventor of chemical warfare.

Kate: I think about that a lot with television. Billy Graham used it to televise his sermons to hundreds of thousands of people, sharing the gospel in a way that was new at the time. He couldn’t be everywhere at once, and not everyone could go to a stadium.

But that same technology was used to create all kinds of immoral or harmful content like scary movies, nudity on TV, and so on. Eventually, it had to be regulated.

Now, we’re seeing a need to regulate some of this new technology, especially with AI. Today, people get scammed with AI-generated videos. It might look like someone’s granddaughter saying, “Hey, send me money to get out of prison.”

Older people see it and can’t tell if it’s real or just AI with cloned voices. That’s where we’ll have to start recognizing that this kind of thing might need to be criminalized. But we don’t have those laws yet.

Thomas: Well, fraud is already against the law, so you can’t legally defraud someone.

Most of what you see on Facebook these days is either from your friends or AI-generated. The big problem with Facebook fraud is that a lot of scammers live outside the reach of American law, and the U.S. government isn’t really doing anything about it.

So we’re talking about billions and billions of dollars in fraud. Most of it actually happens over the phone. It may start on Facebook or through email, but phone calls are the main tool scammers use now.

AI deepfakes are allowing scammers to make you think you’re talking to a human. They can also disguise accents, making someone sound like a native speaker. Then they try to manipulate you either by scaring you or by triggering your greed.

Be aware of scammers trying to feed on your fear and greed or your desire to talk to someone on the phone; you can avoid a lot of these scams. A legitimate company doesn’t want to talk to you on the phone because phone support is expensive. The only people who do want to talk to you on the phone are scammers. Even companies trying to sell you something don’t want to deal with phone calls anymore.

How are authors currently using AI?

Thomas: We’ve talked about some of the scarier uses of AI, like deepfakes, where someone says, “We’re holding your daughter hostage.” That’s terrifying. The way Facebook uses AI to control what you see, what you don’t see, and even to influence your mood or political views is also scary. It’s been happening for over a decade, and it’s deeply concerning.

But there are also uses of AI that are closer to home.

Authors are using AI to help with research, marketing, or even writing or editing their books. Every stage of the process, from idea generation to typesetting, now has some form of AI assistance available.

Different people seem to be drawing the line of acceptability in different places along that chain.

How do you use AI?

Kate: I’ve always been a bleeding-edge kind of person with technology. When AI started gaining attention through ChatGPT, I was a little skeptical. But as we all know, AI has been around for a long time. People are just now realizing that when you talk to your phone and it transcribes your voice into poorly written text, that’s AI at work.

Thomas: It’s all AI. There are layers of AI on top of AI. I find it funny when a critic attacks an author for using AI and posts that attack on Facebook, which is a platform completely controlled by AI. What you see or don’t see on Facebook is entirely determined by Facebook’s AI. These critics are fine with Mark Zuckerberg having AI, but not with regular folks using it.

Kate: It often comes down to money. People are okay using AI to make money but don’t want others to make money from it.

Writing a book today is just one part of the mission for authors. You have to protect your purpose, and AI helps me do that by giving back some of my time.

Authors today wear many hats. We’re writers, marketers, graphic designers, brand strategists, tech support, public speakers, accountants, and business owners. How can one person do all that? I see AI as a team that helps me stay focused on creativity.

If you’re morally opposed to writing with AI (and some people, including some traditional publishers, are), you can still use it for other tasks, like creating graphics or emails. I’m in a round robin with 27 authors where we take turns sharing each other’s reader magnets in our newsletters. That’s 27 newsletters to coordinate.

I volunteered to organize it, partly because I wanted to own the data. I had everyone fill out a Google form with their photo, bio, back cover copy, and links. Then I used AI to take all that information and generate a draft of an email newsletter in my voice. I review the draft, make manual tweaks, click a button, and it generates the HTML for my newsletter. A task that used to take me hours now takes 15–20 minutes. That’s just one small way I use AI.

How can authors use AI for marketing?

Thomas: Marketing is the easiest place to start. Most authors don’t have a marketing person, and many don’t hold marketing in high regard. So they’re not replacing anyone when they start using AI for marketing. They’re just finally doing tasks they knew they should have done.

For building a website, I recommend WordPress with a theme called Divi. I offer a free course on how to build a website with it. That course is still helpful, but Divi now has AI built in. You can just describe what you want the page to look like, and it will generate it for you. It’s like having a webmaster. You can even talk to your site to make changes.

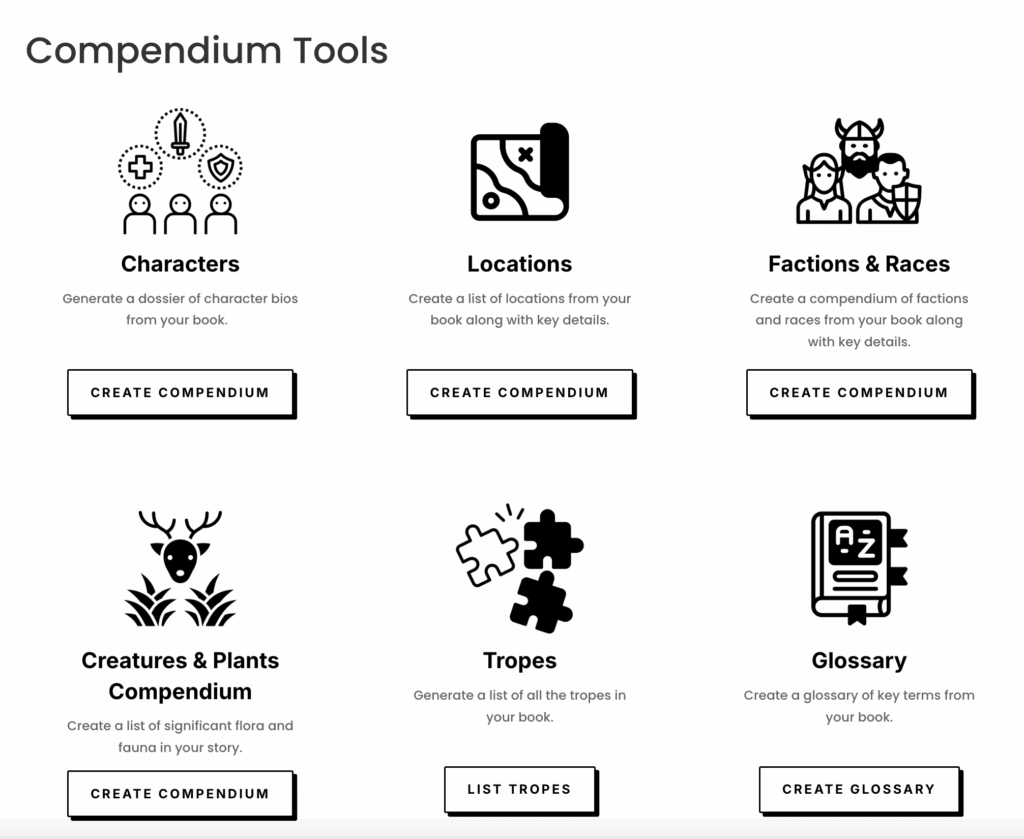

I also built a suite of tools called the Patron Toolbox with over 60 tools that make marketing easier. It includes tools for blurbs, back cover copy, email drafts, subject lines, discussion questions, and even lesson plans.

Kate: One drawback of using AI for marketing is that it often writes vague copy. You’ll see back cover blurbs like, “Can they stop the bad guy before it’s too late?” That doesn’t communicate much and sounds like everyone else’s copy, so you have to be careful.

I also use AI to learn. For example, I use it to teach me how to write better SEO. Back cover copy is now being stuffed with keywords. People search for books online more than they browse in stores. That means the online version of your back cover copy needs to include searchable phrases like “high-stakes thriller” or “reunion romance with a lost baby” to help your book show up in results.

It’s not merely about metadata anymore. The visible copy has to be optimized for search. AI helps me learn how to do that faster. These days, we all need to keep learning new skills to thrive.

How does AI affect discoverability?

Thomas: On my other podcast, we talked about AI Optimization for Authors. It’s all about getting AI to recommend your book.

SEO is really about making your website bot-friendly. We’ve had bots crawling the internet for decades. Making your website accessible to those bots used to help you rank on Google, and now it helps AI tools like ChatGPT recommend your book.

More and more people are moving their searches from Google to AI. I’ve almost completely switched. Google search has gotten worse, while AI search tools have improved. I use Grok with deep search turned on for research. ChatGPT also has a deep research function that’s helpful if you’re using a paid model.

If you’re worried about privacy or about your content being used for AI training, the solution is to become a customer. Free users are the product. Paid users are the customers. From what I’ve seen, AI models train on free users’ data, not paid users’.

What are the benefits of using Perplexity?

Kate: Speaking of moving away from Google, I’ve been using Perplexity for two or three years. It’s like the AI version of Google. I like Grok’s deep search too, but Perplexity lets you save your search conversations.

As a romantic suspense author, I might need to research how a specific kind of bomb works. For example, maybe I need a particular type of explosion that doesn’t destroy everything. I can use Perplexity to learn about that, get procedures for how a tactical team might approach it, and see all the sources and footnotes.

I can then pin that chat so I can come back to it when I write another explosion scene. Google might show you a summary, but it doesn’t save chats in the same way. I find myself going back to Perplexity often when I’m researching details.

How does AI improve search and research?

Thomas: Let’s say you do a search and it doesn’t bring back what you’re looking for. In the past, you might’ve added some Boolean operators or a minus sign, or maybe you used quotation marks to search for a specific phrase. With Grok Deep Search or Perplexity, you can just talk to it and clarify what you meant. For example, you could say, “I meant Roman historical, not Middle Ages,” and it will refine the search based on that clarification.

You can keep building on your original query, which is really useful.

Kate: I use a little shortcode when I’m writing suspense or thrillers. It automatically inserts a note that says, “This is for a novel.” That way, if I start asking how to build a bomb, the AI doesn’t block the response. Once it knows it’s for fiction, it’s usually fine.

Thomas: Another helpful use of AI is continuity support. Now that AI context windows are larger, you can upload your book and have the AI pull out a list of your characters with bios or all the locations used. I just created a Patron Tool called the Character Compendium to help with this.

This is great for creating a reference for yourself or your editor. It might include correct spellings, character descriptions, or pronunciation notes. When you’re six books into a series and want to bring back a character from book two, you might not remember what you originally wrote. A character compendium can help with that.

The newer, larger-context windows can generate a compendium quite well. If you want to do it yourself, I recommend using Notebook LM or Gemini, or you can use my PatronToolbox.com. I always try to use the best model for each task and swap models as they leapfrog each other.

How can Notebook LM help authors revise their manuscripts?

Kate: I’ve been using Notebook LM for a while. I remember showing it to Steve Laube when it first came out a couple of years ago. You can upload a whole book and ask, “What’s the spiritual arc of the heroine?” and it will pull that out. I can ask, “Where are the plot holes?” or “Where should I insert a new subplot?” and it will help me find good places for those changes.

As a traditionally published author, I get editorial letters that can range from one to six pages. I take those requests and use Notebook LM to search my manuscript. If my editor says something needs to be deepened, I’ll ask the AI to find places where that could naturally happen. It doesn’t do the writing for me, but it speeds up the process by helping me locate the right sections. It keeps me from having to reread the whole manuscript again and again.

How can AI help with chapter summaries and timelines?

Thomas: AI is also really good at creating chapter summaries. Authors usually hate writing chapter summaries, but they’re often required for book proposals in the traditional publishing world.

Summarizing a chapter is difficult for most authors, but easy for AI. It doesn’t have to be beautiful prose because it’s just a summary. Think of it like search engines summarizing websites. My Chapter Summarizer tool will spit out one-paragraph summaries for each chapter. That’s a huge time-saver. What used to take authors a weekend can now be done in less than an hour.

Summarizing a rich, emotional chapter into a flat paragraph can feel soul-crushing for authors. It’s all telling and no showing. AI can handle that kind of work so that you don’t have to. No one starts writing because they love crafting chapter summaries.

Kate: Timelines are another area where AI helps. After turning in my manuscript, I’ll often be asked for a timeline of when events begin and end. That’s not something I naturally think about while writing.

Thomas: AI tools help you create those timelines, whether you’re writing a thriller that happens in 24 hours or a fantasy spanning centuries. The Timeline Chronicler tool in my patron toolbox can help with that.

But you can’t just generate a timeline and hand it off. You have to double-check it. If the AI’s version is wrong, it might be that your manuscript is unclear. Maybe you forgot to specify something, or you wrote it inconsistently. Fix the manuscript, make sure everything aligns, then hand the timeline to your editor along with your character and location compendiums.

What are the limitations of AI tools like Notebook LM?

Kate: Notebook LM doesn’t always catch every character, especially if you’re building a compendium with character appearances. So you still need to do some of the work yourself as you go. You can’t just rely on the AI to catch everything.

Thomas: You’re building a document that carries forward into your next book. It gets bigger over time and becomes an asset for you and your editor. It helps ensure your continuity stays strong.

AIs are hyper-rational and great at helping with continuity in storytelling.

How does AI make you more productive as an author?

Kate: When I first started out, the bleeding-edge technique was to create a template. My template outlined what each scene needed. If you’re familiar with how Susan May Warren structures scenes, she refers to these elements as “stakes.”

Whatever method you use, if you have a scene structure, you can say, “Here’s what needs to happen in this scene,” like a mini chapter summary. Then you can ask AI, “How do I hit each of these points?” Things like setting the scene, time, characters, blocking, and all of that.

A lot of authors fall into what’s called “white room syndrome,” where they forget to describe the space around the characters. But if you’re writing a campfire scene and later someone grabs a hot frying pan, you need to have already told the reader that the frying pan was there. If you didn’t, it breaks the reader’s experience and pulls them out of the story.

I use a template and ask AI to help me build out those kinds of details so I don’t forget anything important. If I have a chapter summary from the previous scene, I know what needs to happen next and can build on that.

I also use a brainstorming template where I can copy and paste or use shortcodes.

Thomas: I use a tool called TextExpander. It’s for Mac, maybe PC too. You can create little snippets that expand into full emails or text blocks. For example, I have “-bio” set up, so when someone asks for my bio, I type “-bio” and it fills it in. I don’t have to retype it or look it up every time. It’s all about efficiency.

Kate: That’s AI in action, too. It’s reading what you wrote, running a little program, and expanding it.

Thomas: By that definition, everything on your computer is AI.

Kate: Exactly. It’s a small input that generates a big output, and that’s the goal. I use templates for brainstorming too. You just did a podcast on James Scott Bell’s Write From the Middle. I love that approach. Even if I know where the middle is, I might not know the villain’s motivation, or I might have backstory but not know how the characters will grow.

I use a template to generate ideas to help me nail down what I’m trying to do in each scene or chapter. That way, I’m not just writing pages of unnecessary words. The template helps me stay focused.

How can AI help with story structure?

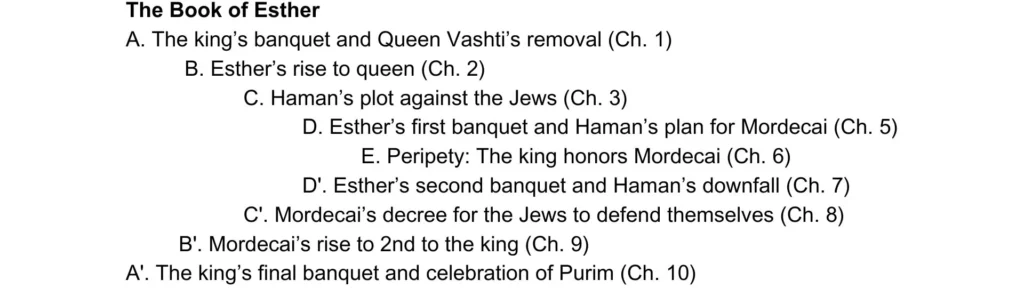

Thomas: AI is very good at structure, both in identifying structure from existing work and helping you build one from scratch. When I did my episode on chiastic structure, I used AI a lot. I asked it, “How does the biblical book of Esther follow the chiastic structure?” and it gave me a beat-by-beat layout, even with indented formatting.

It did the same for Dracula. AI can tell you whether a certain book follows the chiastic structure. It can pull structure from a story or help you create one to write from. Some authors like to use AI to create outlines. They want structure but hate outlining. So instead of wandering through a discovery draft, they prompt the AI.

AI must be guided by your human input. You’ll need to have a sense of where your story is going and what outline structure you want to use. You might tell it to use the outlining strategy from Save the Cat, the Snowflake Method, or another outlining method. You have to be involved.

Some people think AI can do everything better than humans. At the same time, they’ll say AI produces nothing but garbage. You can’t hold both of those ideas. If you’ve used AI to build something, you know it takes work, intention, and money.

AI is not free. Right now, companies are wooing users with free access, trying to get you to commit to one platform. Eventually, they’ll start charging more. And they should.

Who is responsible for what AI produces?

Thomas: To illustrate the idea of responsibility, let’s think about who built Solomon’s Temple.

Kate: The people physically built it, but ultimately, God gave the instructions, and Solomon directed the work. It was a hierarchy of leadership.

Thomas: Exactly. The Bible says Solomon built the temple. It also tells us that David provided materials, the king of Tyre contributed, and skilled workers were named. But the credit goes to Solomon because it was his will that made it happen.

That’s how the Bible talks about kings. Kings don’t do everything; they command others to do things. Even when David is old, we read that he “went to war.” But even when he’s old and no longer on the battlefield, he sends Joab or his mighty men. He gives the orders.

Working with AI is a lot like that. You are responsible, just like a king is. If the troops under your command commit a crime, it’s on you. You’re responsible for justice and consequences.

When you use AI, you are still responsible. Some people think, “I used AI, so the machine is responsible.” That’s not how AI or responsibility works. You’re the one prompting the engine. More importantly, you’re reviewing the output. You don’t just copy, paste, and publish. You revise, verify accuracy, and ensure it’s true.

This requires a mental shift. We don’t think like kings anymore, especially in the U.S. But when you use AI, you quickly start giving it orders. Some still say “please” and “thank you,” but you end up treating it like a subject. You are the king, telling it, “Go make this for me. Go create this.”

Kate: I really appreciate that point. Even if you have help, whether human or AI, you’re still the one writing the book. Tools like ProWritingAid or Grammarly use AI to flag passive voice or other issues. They help you learn, but if you rely on them too much, your skills will atrophy.

AI should be a learning tool, not a crutch. If I let AI fix everything, I’ll never learn not to write in passive voice. You still need to stay in the driver’s seat.

I think of it like driving a car. I’m responsible for where the car goes and for the passengers inside. I have the steering wheel. I need to stay in control and not let AI take over.

A More Dangerous Form of AI

Thomas: I’ve come to see Grammarly as one of the more dangerous forms of AI. I’ve really changed my mind about it over the years. Writing a book with AI by prompting it to write a scene that follows certain beats is less problematic than blindly accepting Grammarly’s changes to something you’ve already written.

When you’re prompting Claude, ChatGPT, or even Grok, you can guide the AI to follow your voice and style. It gets pretty close, and then you can refine it further to sound even more like you. But Grammarly almost always makes edits that erase your voice. There’s a sameness to the writing of people who rely on it.

It didn’t used to be that way. I used to recommend Grammarly wholeheartedly because it highlights things like passive voice. Instead of just making the change, it would link to helpful articles to help you learn the rule and improve your writing. It was an educational tool for authors.

Now, if you’re using the default settings, Grammarly will make multiple changes at once. It will insert commas, fix passive voice, and reword sentences all in one click. Maybe you only wanted two of those changes, but it’s so much effort to separate them that you just accept them all. That’s how your voice gets buffed right out of your manuscript.

I think people are worried about the wrong things. They’re afraid of using AI to generate a paragraph of text, but not afraid of letting Grammarly rewrite one. In reality, the difference is who has the final say. When you use generative AI, you remain in control. But when you let Grammarly make the edits without review, the AI has the last word. It’s far better for you, the human, to keep control so that your voice and perspective are preserved.

We’ve been trained to accept Grammarly’s suggestions because it presents them in the same way Spellcheck did. When I was a kid, if I saw a red underline, I knew I’d made a spelling mistake that would be marked wrong by my teacher if I didn’t fix it. Grammarly triggers that same kind of automatic compliance, even when its suggestions aren’t right or appropriate for your book.

I still use Grammarly, but I’ve disabled most of its features. Now I only accept things like comma corrections. I’m terrible with commas, and Grammarly is great at that. But overall, I’m wary of the platform. I think authors have been too quick to adopt AI spellcheckers and too slow to explore AI writing assistants.

Kate: A friend of mine once sent me a screenshot from Grammarly. She had written something like “out of the corner of his eye, he saw movement,” and the AI flagged it as overusing the word “eye.” Its suggested replacement was “Out of the box of his eye.” It focused on the wrong word entirely, and the suggestion made no sense.

That’s why I think it’s worth learning how to fine-tune the AI models you use. If you write with AI, rather than letting it write for you, you can get much closer to matching your tone, cadence, and even your genre-specific voice.

Anyone can prompt ChatGPT or another AI, but when you learn how to prompt effectively or fine-tune your prompts, you won’t get generic, AI-sounding copy. You’ll start to get something that sounds like you.

As AI continues to improve, fine-tuning will only become more powerful. Just like you’d invest time in marketing, it’s also worth investing in finding your author brand voice. Are you funny? Dry? Sarcastic? Deep and sentimental? Fine-tuning a model to reflect your personal style means you won’t get the same results as everyone else using the same prompt.

Grammarly is replacing your unique voice with a generic one. That’s something authors really need to be aware of.

How would you recommend an author start using AI?

Thomas: For someone who’s intrigued by AI but hasn’t used it yet, where would you suggest they start?

Kate: To dip your toe in, I’d say start with ChatGPT. The next time you write an email that feels a little long, copy it into ChatGPT and prompt it by saying, “Below is an email I wrote. Can you make it more concise and clear, but keep my voice? Maybe add humor (or don’t). Just make sure the grammar is correct.” That gives you a sense of how your writing could be clearer.

There are patterns you’ll start to notice. AI has certain “isms” you won’t recognize until you’ve used it a lot. AI is helpful when you’ve got a long email and want to make it tighter and more readable.

It’s a great starting point. You’ll begin to recognize patterns, like how it loves hyphens. I don’t know who trained OpenAI to hyphenate every sentence instead of using commas, but don’t fall for it. If I see an email with eight hyphens, I know AI wrote it.

Thomas: I have a theory about the hyphens. Many AI tools overuse hyphens. Hyphens are common in formal writing, which was heavily represented in the AI training data. Public domain texts, especially pre-1925 books, are safe legally, so they’ve definitely been included in training the AI models.

This is also why AI is surprisingly good at Christian theology. It has read the works of the church fathers, though maybe not the most recent ones. In that older writing, hyphens show up constantly. When AI uses them, it sounds formal.

Now, if you’re an author, you may already use hyphens. But normal people (non-authors) don’t use hyphens in emails or on social media. That’s why it stands out as an AI tell. In a book, though, it doesn’t look odd at all. In fact, hyphens are common in printed books. Typesetting tools even hyphenate words across lines.

Kate: That’s a good point. I was thinking about Jane Eyre and the writings of C.S. Lewis. Both authors use lots of hyphens in their work where we’d now use commas or parentheses. I use hyphens in my writing, but now I’m second-guessing it. Will my editor think I used AI? Should I switch to commas? I might be overthinking it, but that’s probably another episode.

What happens if AI is trained only on public domain works?

Thomas: AI is already shaping language, and there’s a big push to keep copyrighted works out of training data. But people pushing that idea often don’t understand how large language models work. Most can’t even explain the difference between machine learning and an LLM.

If you purge all copyrighted content from the models, you’re left with pre-1925 writing. That means all modern ideas, including feminism, are gone. You’re back to 18th- and 19th-century worldviews. Models become more conservative and religious.

Some people use theological language like “original sin” to describe AI’s training on copyrighted works. That terminology itself shows a misunderstanding because machines don’t sin; only people sin. You don’t blame the knife; you blame the person holding it.

So be careful what you ask for. Do you really want a large language model trained only on Victorian values? Honestly, I’d be curious to see that.

Kate: Me too. The language would be different, and the insults might be more refined. But if we remove modern works, there’s a huge gap. AI would be missing context for how we got to where we are now. You’d get a mashup of Victorian phrasing and King James–style language.

Thomas: I created an AI called TwainBot, trained on all the writings and biographies of Mark Twain. You can send him a scene and get feedback in his voice or ask for advice. It’s programmed in the vernacular of the 18th century and uses his witty style. It pulls from his speeches, letters, and books.

It’s fun, but it’s one of the least-used tools I’ve built. People don’t want that Victorian voice. Deep down, many of us feel like we’re failing to live up to the standards our ancestors set. They built cities out of wilderness with their bare hands. Meanwhile, we can’t keep those cities from falling apart.

There’s a discomfort in that, so we avoid thinking about it. It’s easier to dismiss our ancestors as evil than to confront how great they were and how we’ve fallen short. But we have created AI, and it can make us more productive. That productivity gives us more time to write, to be with family, or to make money in other ways.

If you’re the only farmer in town with a tractor, you’ll have more time than those still using a hoe. The tractor is a huge advantage. Don’t listen to someone with a tractor telling you it’s evil to own one. They may have an incentive to keep you down so they can rise.

There was a study showing that in jobs exposed to AI, wages have gone up by as much as 50%. People using AI are making more than those who aren’t. This isn’t new. Every technological innovation that boosts productivity leads to higher earnings for those who adopt it.

Farming is a good example. One farmer today produces more and earns more than ten farmers did a century ago. That one person now does the work of ten and gets paid like five. He’s better off, but the other nine have had to find new jobs in cities. That’s how it’s always worked. There’s nothing new under the sun.

So don’t build your worldview on AI around a 1980s action movie. That’s not a solid foundation.

Kate: If you think AI is just a shortcut to do the writing for you, you’re missing the real transformation. This is a business model shift. And like you said, if you don’t shift with it, you’ll be left behind.

Connect with Kate Angelo

KateAngelo.com: Sign up for the round robin to receive free books every month.

New Patron Tools for Writers

Structure Analyzer

With this tool, you upload your manuscript and select the major story structure you’re using, such as Save the Cat, Three-Act, or Hero’s Journey. The Structure Analyzer will evaluate how well your story fits that structure and offer suggestions for improving it.

Not a Developmental Editor

This tool reads your manuscript and generates a report offering feedback on how to strengthen your writing. It’s fast, insightful, and has quickly become one of our most popular tools. It’s ideal when you need developmental-level feedback without waiting weeks or paying hundreds of dollars.

Not a Literary Agent

This tool offers professional-level advice on a range of topics. It can evaluate your manuscript, help you understand publishing contracts, and even assist in drafting a rights reversion request letter. Authors have been giving incredible feedback on this tool. While it’s not a replacement for a real literary agent, it’s a great option when you need quick guidance.

AI Thomas

AI Thomas is a chatbot trained on every episode of Novel Marketing and every blog post from The Christian Publishing Show. You can use it to ask questions, get advice, and dig into marketing topics. Trained on over 500 episodes of content, AI Thomas is like having instant access to everything I’ve ever taught, available 24/7.

There are more than 60 tools in the Patron Toolbox, and more are being added regularly. If you want to explore these tools or start using them today, head over to PatronToolbox.com.

I have been using AI for a lot of my marketing stuff, and I have liked the results. I would like to use a paid model, but I don’t want to pay for a bunch of them. What is the difference between the models and what is worth paying for?

I recommend starting out with something like Straico. https://www.authormedia.com/straico (Affiliate Link)

Straico gives you access to all of the paid models for $12.49/mo and you can ask multiple models the same question at the same time. This will help you figure out which model you like best.