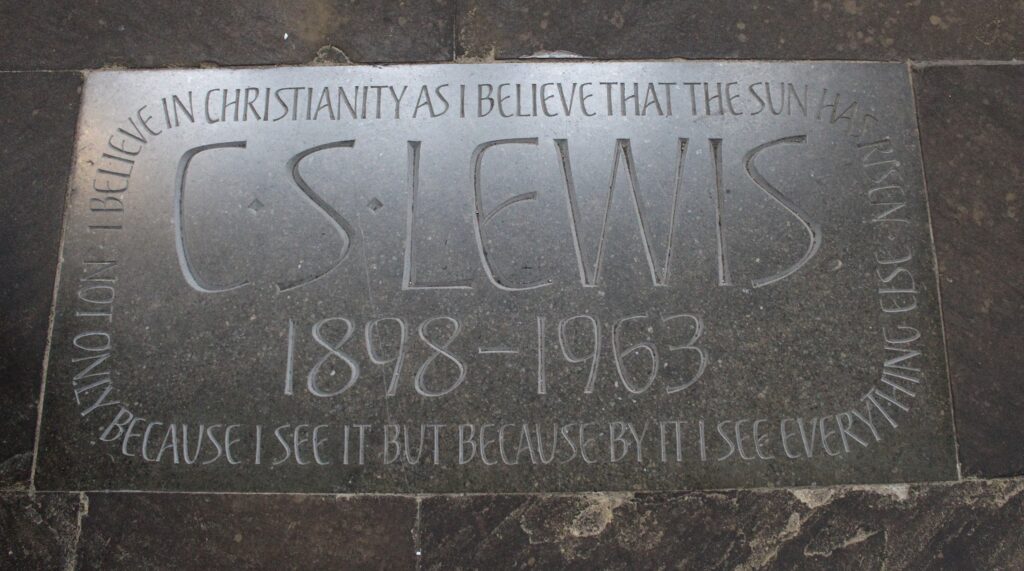

On the memorial stone of C.S. Lewis in Westminster Abbey, this quote is engraved:

“I believe in Christianity as I believe that the sun has risen, not only because I see it but because by it, I see everything else.”

For Lewis, Christianity was the lens through which he saw the world and wrote his books. Lewis had much to say in his various books, and as an author his Christian worldview influenced everything in his fiction.

Many authors’ understanding of theology doesn’t go much beyond the sinner’s prayer, and their stories reflect that shallow understanding. They end up writing the same simplified message over and over.

We all have a worldview. We all have a lens through which we see the world; and it will impact our writing, whether we know it or not. Fiction is a great place to explore a worldview, especially speculative fiction.

Communicating an intentional message in your novel requires you to know what you believe and why.

Christian fiction writers often struggle to maintain a balance between boldly weaving faith and biblical themes into their writing and sounding preachy or didactic. Few authors can do it well.

Because many Christian authors don’t want to offend anyone, they err on the side of avoiding deep theological issues. On the other end of the spectrum, some authors use clichéd ideas and shallow characterization to make their books sound “Christian.”

How do Christian fiction writers address important issues of theology and apologetics in their stories without writing them like a Sunday school lesson? How does your Christian worldview impact your writing as an author?

One author who knows her way around worldview is L.G. (Laura) McCary, who does not shy away from discussing deep theological issues in her novels. She is the author of That Pale Host, a psychological suspense novel with a supernatural twist, and she’s the social-media manager and staff writer for Lorehaven.com.

What does worldview mean?

Thomas Umstattd, Jr.: What do worldview and apologetics mean to you?

Laura (L.G.) McCary: Worldview and apologetics refer to knowing what you believe and why you believe it, so you can communicate it appropriately. I love knowing why I believe a doctrine and where it originated.

Thomas: A Christian worldview affects an authors politics and every interaction you have.

Worldview is a relatively new subject that Christian students learn about. I received worldview training in high school, but my parents did not. When my parents were going to school, there was an assumption that everyone had the same worldview.

But we don’t.

There are many worldviews, such as Communism and cosmic humanism (also called New Age), which are complete worldviews.

Sadly, some Christians have a New Age worldview. They’ll talk about “looking to Christ in you” and “being true to yourself.” These New Age concepts have Christian language attached to them, so they’re sometimes hard to discern.

Laura: You’ll also hear them talk about “Christ consciousness.” Some of the language sounds right, but it’s off. When you poke it, you can see it’s coming from a completely different worldview. It’s not from Scripture at all.

Thomas: That’s right. The same is true with Communism.

In Acts chapter two, you’ll read that the early Christians were sharing what they had, and some people take that to be a plug for Communism. But there’s a big difference between me choosing to share what I have and you using the threat of force from the state to take what I have and give it to somebody else.

If you don’t have a sophisticated understanding of worldview, Acts might sound like Communism.

But it is not the same.

How do authors incorporate Christian worldview into fiction?

Thomas: What does it look like to write a novel that expresses your worldview?

Laura: It starts with being confident about what you believe, so you can express it through storytelling. If you are not confident in your faith and the doctrines you believe, your uncertainty will show up in your fiction.

I read a well-known, young-adult series where I could tell that the author had questions in her mind while writing about the nature of humanity and nature versus nurture.

She did not resolve those issues in her mind by the end of the series. It was frustrating to read. I have a psychology degree and have thoroughly thought through those issues. When I reached the end of the series, I thought, She didn’t know what she thought the whole time she was writing.

If you don’t know what you think about a particular topic, you won’t be able to communicate well through your fiction because it will come out muddled. It’s easier for Christians to see examples of that muddled thinking in secular fiction than in our own fiction because we agree with ourselves.

Thomas: In many ways, we’re currently seeing a caricature of ourselves in secular fiction. For decades, the big critique of Christian fiction was that it was too preachy and it was the same message over and over.

If you’ve watched movies or shows written in the last several years, you know they’re all touting the same message of diversity, inclusion, and equality. In fact, the critics are even mocking the repetition, and it’s turning away audiences. Ratings and sales are down across the board.

Today a number-one hit movie only requires $20 million in sales. Two years ago, $20 million wouldn’t have ranked in the top ten. There’s been a complete collapse in the connection with the audience.

I heard someone explain the phenomenon to a Christian audience. He asked who had seen the movie X-Men 2, and many people raised their hands.

Then he asked who had seen Broke Back Mountain. Almost no one raised their hands. Both movies had the same message; but in X-Men 2, the message and worldview were incorporated organically into the story.

X-Men 2 was entertaining, while Broke Back Mountain felt like a sermon.

People don’t want to buy tickets to a sermon, but they do want to watch a fun movie. X-Men 2 was effective partly because it was speculative, which meant that the mutants were a metaphor. The message becomes less preachy if you work it in organically.

What tips do you have for a Christian trying to organically incorporate their worldview into a great story?

Laura: Speculative writing has the unique capability of disarming readers and getting them interested in something they might not otherwise accept.

Books like 1984, Brave New World, and Animal Farm are excellent dystopian books, which aren’t Christian; but they’re written from a clear point of view.

Those authors, Huxley and Orwell, had specific purposes for writing those stories. But the stories disarm your initial argument because they are set in a different world. Animal Farm is about animals; and because the characters aren’t human, the message gets past your internal gatekeeper.

I’ve noticed this a lot with my children. For example, the Kung Fu Panda TV show series had several issues I had to carefully point out to my kids. I stopped the show to point out that the characters were subscribing to Eastern philosophy, which is neither true nor compatible with our Christian beliefs.

Since the show is a cool story with pandas and snakes doing karate, kids get excited about i;, and their internal gatekeepers can be caught off guard.

As a Christian, you must know that incorporating your worldview is powerful; but only if you deliberately try not to be preachy.

Thomas: The key is to be specific. The more specific you are, the less preachy you sound.

For example, I’ve wanted somebody to address the fallacy of “Well, we just need to do something.” Characters and real people commonly say it, as if it doesn’t matter whether what we’re doing works. We just need to do something.

The problem is so big and terrible that we just need to “do something.” But the truth is, if what you’re doing isn’t working, then it’s harmful because it’s keeping people from looking for the actual solution.

Doing “something” isn’t enough. We need to solve the problem. There’s a big difference between just doing something and actually fixing the problem. That fallacy could be easily explored in fiction in a thousand specific settings.

Specificity keeps it from feeling preachy because you can write about real life and people’s real problems. It’s not a vague sermon with Christianese platitudes.

Laura: Certain movies use vague platitudes like “be yourself” or “believe in your dreams.”

I’d rather see Tony Stark at the end of Endgame, knowing he will sacrifice himself for the entire world even though he’ll lose everything he cares about.

The idea of sacrifice and growth is a Christian concept. Tony Stark’s character arc moves from selfishness to selflessness, from arrogant jerk to hero who saves everybody to his own hurt. That’s a Christian idea.

I get frustrated when I see movies or cartoons that could be so good; but in the end, the writers just slap on a platitude like “everything will be fine.”

They begin with a specific message about loving your family or respecting your parents, but then it becomes a vague “everything’s fine” message. Specificity is important.

Thomas: Tony Stark was specifically flawed. He was arrogant, selfish, and prideful. Throughout the story, he learns to repent of those flaws, make amends, and suffer the consequences of his flaws.

Compare that to the recent remake of Pinocchio.

The original story of Pinocchio was a moral story. Most Disney stories have awful worldviews, and I got my initial worldview education by discussing the worldview problems of Disney films that most people loved.

In the Pinocchio remake with Tom Hanks, Pinocchio is a victim. He’s not choosing to do evil. The children aren’t drinking alcohol and smoking cigarettes. They’re drinking root beer and smashing clocks.

By diminishing the evil, the writers actually ruin the whole message. There was no point.

That’s why it went straight to Disney Plus. They did the market research and knew they had a stinker on their hands, but they didn’t know why it wouldn’t do well.

The problem was that they lost the powerful, ethical core of the story, where you were encouraged to do more.

In contrast, the most recent Spider-Man movie had a powerful moral message about being compassionate to the poor. One character really represents compassion to the poor and suffers for it.

Many writers are afraid to let their characters suffer.

If you don’t let your characters suffer, you’re subscribing to the Disney version of a Christian worldview, where suffering is something to be avoided.

Christians often see God as the one who takes our suffering away, and sometimes he does. But he also brings suffering. In the Old Testament, God is the source of suffering as much as he is the alleviator.

To explore that theme in our fiction, we must let our characters suffer without putting a Disney gloss on it.

How do we explore suffering in fiction?

Laura: We must have a proper understanding of the theology of pain.

Atheists often say, “Good people suffer, and bad people win; and that proves God doesn’t exist.”

But the problem of pain doesn’t disprove God. It actually proves that our God is with us through our suffering and pain.

In my novel That Pale Host, the main character, Charlotte, struggles with post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, and anxiety. She’s struggling to be a decent mom, to take care of her kids, and to do all the normal things. She’s also a strong, dedicated Christian who attends church every Sunday.

I wrote her character partially out of my own experience. I’d been through what I call my kintsugi story.

There’s this concept in Japanese pottery called kintsugi, where broken ceramic is mended with gold lacquer so that it becomes more valuable because it has been broken. All those beautiful cracks are gold.

When I was writing my story, I wanted to convey that God takes our most painful circumstances and uses them for his glory and our good, even though it may not make sense when you’re going through it.

The characters in my novel don’t get every circumstance perfectly resolved. But I am coming at my story from a deep abiding trust that God is with me in my pain, that he loves me and never abandons me. He is always doing something for his glory and my good.

Thomas: God doesn’t keep you from going into the valley of the shadow of death; but when you’re in the valley, he’s with you always.

Allowing your characters to go into that dark valley, into the dark night of the soul, makes them interesting.

Laura: A lot of Christian fiction irritates many of us because nothing bad happens to the characters, or they don’t do anything bad. Authors who like that aren’t subscribing to a Christian worldview.

Thomas: That’s true. The cause of PTSD for most people, especially military folks, isn’t witnessing evil. It’s participating in evil. After a war, people have to figure out how to live with themselves after doing an evil they never thought they’d do.

Interestingly, C.S. Lewis allows his characters to do evil things.

For example, Edmond is a terrible person. He betrays his siblings to the White Witch and is terrible the whole time.

As I was rereading the series, I began to think Edmund was a hopeless sociopath. I had just read The Sociopath Next Door, which posits that sociopathy is an illness, rather than a choice, and there’s no cure.

But as I read the Narnia books, I realized that although Edmund was a sociopath, he had an encounter with Aslan; and after that, he was no longer a sociopath. I was reminded that God is more powerful than sociopathy.

The secular worldview says there’s no cure for a sociopath. There’s no fixing it.

But the Christian worldview says all of us, even authors, are sociopaths to one degree or another, and we all need Jesus to change our worldview and how we approach the world.

Lewis allows Edmund to be a vindictive sociopath who is a cruel bully to his little sister so that his transformation makes him a super compelling character.

Each of Lewis’s children has their own moral journey of choosing to do right and struggling with the temptation to do evil.

Laura: Same thing with Eustace. I deeply identified with Eustace, especially as I went through some hard things as an adult. In the story, Eustace has become a dragon. He’s miserable and doesn’t want to be a dragon anymore.

As he’s crying big dragon tears, Aslan comes and says, “You need to be cleaned.” Eustace tries to take off his dragon scales but can’t. Aslan finally says, “No, I have to do it for you.” Having his dragon skin removed is painful for Eustace; but when it’s off, he’s himself again.

I felt that way about some sin and pride I dealt with when my husband was a pastor. God used some hard circumstances to scour away my sin, and it hurt. But I kept thinking, “When this comes away, when it’s finally gone, I’ll be who God wants me to be. I’ll be myself again. The self that God made.”

Those images are only possible if you deeply understand who God is, why he made you, what he expects of you, and what Scripture tells you about yourself. Lewis is unique because he’s an amazing apologist, theologian, and storyteller. The scene is so powerful because he deeply understood those things.

Thomas: In your story of struggling with pride, God was the antagonist. You didn’t want the suffering. He was opposing you and your pride.

That’s what we see in Lewis’s stories. Aslan is often the antagonist getting in the way of what the children want more often than he’s helping them. I think that’s why Aslan works.

Christian authors often fear putting God in their stories because they don’t know how to do it without having God solve all their characters’ problems. If that’s where your story is headed, your theology is not well developed.

Putting God in your story will add problems for your characters because God has his own ways. He’s not there to simply help us do what we want. He’s doing his own thing and working to get us on his team. It’s not as if you have superpowers when God is on your team. It’s God who has the power, so go with him.

During the Civil War, one of Abraham Lincoln’s advisors mentioned that God was on the Union’s side. Lincoln replied, “Sir, my concern is not whether God is on our side; my greatest concern is to be on God’s side, for God is always right.”

That worldview shift is important. Even in the Bible, we see Joshua asking the commander of the Lord’s army whether he was with Joshua or the enemy. The angel basically says, “Neither. I’m on God’s side.”

Even though Joshua was God’s servant, and God helped him defeat Jericho, God also fought against Joshua in the next battle of Ai.

Novelists need to be familiar with the story of Ai and how God opposes people as much as he helps them. In reality, his opposition helps us to obey him.

I’ve noticed several prominent, secular worldview themes in novels, movies, and TV shows; and one of them is a theme of “no redemption.” Once a character is evil, they’re always evil. They can’t be saved or forgiven. You never see a victim forgive a perpetrator.

In our current culture, once you’ve done evil, you’re canceled. There’s no redemption or forgiveness.

Laura: That is such a dangerous, evil idea to put into the culture.

I have not watched The Handmaid’s Tale because I am not interested in slogging through that. However, I saw a clip where one of the main characters, June, forces a young girl to kill someone. And June’s expression says, “Good girl.”

It was the most chilling clip I’d ever seen because, in The Handmaid’s Tale, no redemption or repentance is allowed. It’s all vengeance.

I’m frustrated with that whole message. It’s a dangerous narrative, especially since that whole story is intended to portray Christians as awful people who should be destroyed. It’s deeply disturbing, and the fact that it’s such a popular show scares me.

It’s important to analyze messages and themes in the shows we watch.

For example, I would’ve never watched Game of Thrones, not mainly because of the porn, but because it is nihilistic. There are no good people and no good endings. Every single character in that story is dark, gross, and awful. George R. R. Martin is doing that on purpose. Nihilism is his worldview. The dragons might be cool, but there’s a heavy dose of dangerous lies being handed to you along with those dragons. Not to mention the porn.

Thomas: Plus, he can’t end the story because nihilism doesn’t lead to emotionally satisfying conclusions.

Laura: Nobody will be happy with that ending. Someone else will have to finish it for him.

Thomas: If I were his marketing person, I might recommend not ending it. Sometimes ending a story can torpedo the sales of all the earlier stories.

Pop culture doesn’t know how to stick the ending because they don’t have a worldview that leads to a satisfying ending.

Christians have an advantage in that our worldview leads to really satisfying endings. It’s not the destruction of evil people. It’s that evil people can be transformed through the power of the gospel.

A Christian worldview teaches that we’re all evil from the beginning. Being a part of a marginalized community doesn’t make you good. Being oppressed or poor doesn’t make you good. None of those is the path to redemption.

The path to redemption is through the cross of Jesus; and it’s open to everyone, even the oppressors.

The fascinating thing about the gospel and the early church was that it included Greeks and Jews. Oppressors and oppressed, masters and slaves, men and women all received forgiveness and redemption. It wasn’t a gospel only for slaves, women, or Jews. The gospel is for everyone.

The gospel is powerful and appealing.

As people spend time in the darkness of the woke worldview that lacks redemption and forgiveness and become acquainted with how they don’t live up to their own worldview, they’re going to become increasingly desperate for true redemption and forgiveness, which their woke religion cannot provide.

Wokeness is emerging as a new religion, and people will thirst for the living water. We need to be there to offer it to them. That means being friendly. Mocking somebody in their sorrow is not the path to reaching them with the gospel.

Laura: That goes along with your Ten Commandments of Book Marketing, including “Love thy reader.”

If you want to write stories that make a difference in people’s lives, you must take them seriously. You must know what they think and why, and then you must respect it enough to represent it properly in your fiction so that when your character changes their mind, it’s a convincing transformation.

I read a book a few years ago for Lorehaven that attacked sexualism and woke ideology in a dystopian world. I could tell that the author knew what he believed but could not understand the worldview of the people he was talking about. As a result, his characters came off as cookie-cutter.

He desperately wanted to show his opponents that their beliefs were dangerous and harmful. The author wanted to invite them to the Christian worldview, where there is healing and love. But no one on the other side of that debate would have read his book because of how it was written and how it treated the other side.

Thomas: Your opponents can easily dismiss the argument by honestly saying, “That’s not what I really believe.” At that point, they’re no longer listening.

I recently read The Abolition of Man by Lewis. It’s a nonfiction book, and Lewis really tries to steelman his opponents in the book.

It’s easy to put together a straw man and beat him up, but there’s no victory in that. Lewis was not looking to beat up a straw man, and he didn’t need to.

If you’re a Christian who is rooted in the Bible, you have a strong worldview. You don’t need to straw-man your opponents because you have the truth on your side. If you feel like you need to straw-man your opponents, maybe you don’t understand your worldview well enough. Perhaps you need to learn to understand your opposition to find out what they’re saying. If that feels threatening, you need to understand your own worldview better.

Christians are fond of the myth that bank tellers only handle real, legitimate money, so they’ll know immediately when they feel or see a counterfeit bill. But that’s not true. Bank tellers are trained by feeling a real dollar and feeling the counterfeit. They study real and false currency.

But be careful as you study your opposition’s worldview. You don’t want to go down the path of Saruman, who got so deep into studying the origins of Sauron that he ended up corrupting himself.

Laura: I am interested in what I’d call Christian-adjacent sects like Jehovah’s Witnesses, the LDS church, and some Christian science. Those sects fascinate me because they twist Christian language from the Bible.

If you want to talk to a Jehovah’s Witness about what you believe, it helps to understand their terminology and where they’re coming from.

In my novel, one character is a hyperconservative fundamentalist. As the story progresses, he gets increasingly picky about points of doctrine and issues that are clearly openhanded issues in Scripture.

In my opinion, I know people in real life who are extremely conservative and who have taken things too far. I did not write that character well the first time; and several readers told me, “That came off fake and paper doll.”

I had to sit down and think about why someone would find those picky issues so important. Why would he care about those things so much? What attracted him to it? When I did that, I felt compassion for the character instead of just assuming he was stupid.

It’s easy to get frustrated with people. Our Internet culture yells at each other most of the time. If you get most of your understanding about your opposition from the Internet, you’ll think everybody’s always angry.

Most people, whether Christian or not, are softer; and their beliefs may be less cut-and-dried than you’re being led to believe.

We need to recognize that almost everybody is trying to learn and grow.

World-Building

When I start world-building for my stories, I want to make sure each character feels real. If I were to sit by them in church, I’d recognize them. I base my characters on real people.

Thomas: Each human believes they’re the hero of their own story. Our own actions make sense to us. No one sees themselves as the villain. Even actual villains don’t see themselves as villains.

In Hitler’s worldview, there was an evil conspiracy of Jews taking over the world. And he was the one person with the courage to stand up and save the world from evil Judaism. He was deadly and terribly wrong; but in his own mind, he was the hero with the courage to fight the “evil.”

Your characters’ actions need to make sense to them, which means they need to make sense to you when you’re viewing them from their perspective. It doesn’t mean their actions are right; but in that character’s mind, their action must make sense.

Portray Evil Accurately

There’s a difference between speaking the truth in love and speaking an incomplete truth. For example, in the New Testament, the demons only speak the truth about Jesus. And yet Jesus often silences them.

They proclaim Jesus as the Son of God, and he tells them to shut up.

Why?

The most poisonous lie is an incomplete truth or a truth spoken out of malice.

The demons weren’t declaring him the Son of God to support him. They were proclaiming it so the crowds would stone Jesus.

It’s possible to wield truth, or part of it, as a weapon against others. Demons wielded a sliver of truth as a weapon against Jesus to undermine him. He silences them because “his time had not come.”

We tend to forget that Satan is an “angel of light.” He’s beautiful. Most of what he said was true when he spoke to Eve in the garden of Eden. It was just slightly twisted.

It’s those slightly twisted truths that are most dangerous. Eve did learn the knowledge of good and evil and became like God in that way, but she also died. She didn’t die right away; but she still died, and death came into the world.

If you want to portray evil correctly in your novel, you must be willing to let evil be an “angel of light” who proclaims a slightly twisted truth.

Write a Convincing Villain

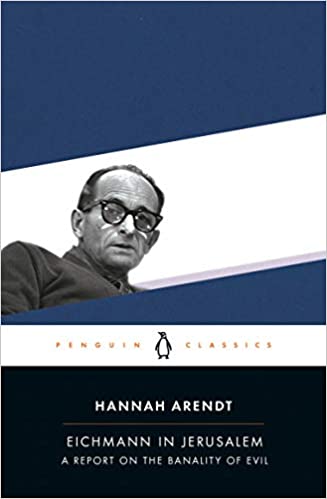

Laura: I thought about that while listening to Eichmann in Jerusalem, which is about the trial of Adolf Eichmann, the architect of the Final Solution to kill Jews during the Holocaust.

He was convinced he did nothing wrong. He said shocking things while he was being interrogated. He said, “I didn’t kill anybody. I just made sure the cars ran on time. I made sure the trains were available. I didn’t do anything wrong. I was just a functionary. I didn’t do anything at all.”

It was infuriating. I had to take it in small chunks because I kept getting angry. But the thing is, it was logical to him. In his mind, he didn’t kill anyone. He sat at a desk during the entire war and made phone calls.

Thomas: Everybody has somebody else they could blame.

Laura: Just like Eve blamed the serpent and Adam blamed Eve. We all can point to something else and explain away our actions.

When writing villains, it’s important to delve into your sinful heart.

I could make my character and story work because I delved into my pride problem. I allowed myself to explore what I would have done apart from Christ. How would I have behaved? How would I have treated people?

If God had not rooted pride out of me, what would I look like? Without Christ, I can be a vindictive and vengeful person. I was willing to pull out the corpse of my old self and put it into the character. You know the depths of your own depravity better than anyone else.

You may not be Hitler, but you know all the impulses in your own heart. When you put those into a villain, he becomes real, honest, and scary.

Thomas: I don’t think we actually believe that we’re evil. Some of us know that some of the time; but most of the time, we feel like our actions and thoughts are justified. We deceive ourselves by saying, “I’m not as bad as the next guy.”

Laura: I agree, but you need to recognize that you are the evilest person you know. When I’m writing, I get honest with myself and God about the ugly things because he already sees them.

Thomas: Remember those motivational posters of the 90s that featured a word like “Teamwork” and a photo of people working together?

There was a reaction to that in a series of demotivation posters. I had one in my office. It was a picture of a raindrop pouring off a leaf, and it said, “Irresponsibility: No single raindrop feels responsible for the flood.”

It pointed out that we don’t acknowledge being part of the problem. When you’re sitting in traffic complaining about the traffic, you don’t usually consider that your car is part of the traffic problem.

Creating characters is an opportunity for us as authors to hold up the mirror of the law so that people can see the sin inside their own hearts. It’s easy to point to the villain and call him evil, but it’s more powerful and redeeming when we recognize “I am Edmund. I am Eustace.”

The more three-dimensional the character is, the more our readers can see themselves, not just in the hero but also in the villain.

There’s power in a tragedy, and tragic stories help us change our ways.

Laura: Movies like A Quiet Place portray an awful world where everything is terrible. But then there is a beautiful moment of sacrifice and love at the end.

Those dark and scary stories illustrate our sinful nature and God’s incredible grace better than fluffy bunny stories. I need an occasional fluffy bunny story, but I know that God works through the darkness and hard things.

Thomas: Character is developed in the suffering. Understanding the lies helps us better understand the truth we study. We must study them both.

Power for Good or Evil

Thomas: The difference between Hitler and most of us is power. The only thing keeping us from doing more evil is that we’re not more powerful.

Many of us believe that we could do more good if we only had more power. But what if more power would only enable us to do more evil?

Laura: That reminds me of Sam in Lord of the Rings. When Sam was holding the ring, he thought he could be the best gardener that ever was. He would fill the whole of Middle Earth with a garden.

But then he says, “No. That’s not true. That’s a lie.”

It’s the most beautiful moment.

I recently discovered something Tolkien said in a letter to his friend Fr. Robert Murray. He said, “The Lord of the Rings is of course a fundamentally religious and Catholic work; unconsciously at first but consciously in the revision.”

The Lord of the Rings is of course a fundamentally religious and Catholic work; unconsciously at first but consciously in the revision.

J.R.R. Tolkien

I suspect some of the frustration people have with new versions, like Rings of Power, is that they don’t understand it’s fundamentally a Christian story. It’s fundamentally Catholic as well. And when you see moments like that, Tolkien is referring to the total depravity of man and the brokenness of our world.

Those concepts are placed in his story unconsciously at first and consciously during the edit.

That’s what Christian writers should do. Pour out your first draft, and your beliefs about Jesus and Scripture will emerge regardless. When you go back to edit, you consciously refine it so that you know it will be edifying to your readers.

Thomas: It reminds me of Proverbs 16:9, which I’ve meditated on for a long time. “We can make our plans, but the Lord determines our steps.”

That feels backward to us. We want to seek God for the big picture and then handle the little picture ourselves. But Proverbs 16:9 says the opposite. You write the first draft, but then you partner with the Holy Spirit in the detailed revisions.

Where can authors get apologetics and worldview training that teaches the difference between secular humanism, cosmic humanism, and biblical Christianity?

Laura:

- WomenInApologetics.com

- Stand To Reason

- Reasonable Faith with William Lane Craig

I’m creating an apologetics and theology course for Christian speculative authors. Our theology shapes our worldview, which shapes our world-building, so we need to know what we believe.

Thomas: I’d also recommend WORLD magazine. They have a fantastic daily news podcast called The World and Everything in It. They present news from a biblical worldview. It’s illuminating when you compare it to the secular, humanistic worldview or the cosmic, humanistic worldview you hear on the secular news.

I also get news from the Wall Street Journal and NPR. Those sources have helped me understand my worldview better. I get different perspectives on the same news story.

The Daily Wire is not biblical but comes from a secular, conservative worldview.

Getting your news from various sources will help you understand your own worldview. If you don’t study your own worldview, you’ll end up copying and pasting what you consume. FOX and CNN offer a twisted worldview, and they will really mess you up if they’re your only sources of news.

Laura: Your worldview matters. Whether you recognize it or not, it will leak into your stories; and somebody else will notice and ask you about it.

When marketing yourself to agents and editors, they’ll want to know what to expect from you and your worldview. If you don’t know what you believe or why, you cannot effectively market yourself or explain what you care about.

Thomas: It’s true.

My last advice is to make friends with people who disagree with you and spend time listening to them.

One of my best friends is an agnostic/atheist. We disagree quite a bit, but we go to breakfast regularly and discuss philosophy, worldview, and religion. He asks hard questions. As we try to understand each other, we each understand our own worldviews better.

If your worldview can’t stand up to critique, it’s not a strong one. This emerging woke religion does not handle critique well. Instead of responding to a critique, it destroys those who critique it. It’s not fully fleshed out as a religion.

If you want to have a stronger worldview, you must be willing to withstand critique. Critique forces us to return to the Bible and ask our pastors hard questions, both of which are good.

Laura: If you avoid talking to people you disagree with or fail to make friends with people who think differently, I think that’s evidence that you have a tame faith. Christians worship the Lion of Judah. We should not be afraid of hard questions.

Don’t be afraid of being challenged and making proper adjustments in your worldview.

I’ve created a handout with three world-building questions that you might not find in other places, that specifically relate to important concepts in Scripture. You can find it at www.LGMcCary.com/christianpublishingshow.

You can download the handout and receive updates when my worldview course for authors is available.

Connect with L.G (Laura) McCary at LGMcCary.com.

Really good discussion!

Just caught this today. I don’t write speculative fiction and, since I’m mostly reading in my genre these days, don’t read much of it either. But this discussion is one I would recommend to any Christian author. And, perhaps, any Christian in general, too.

So good!