Have you ever read a book where the characters didn’t seem like real people?

The author who wrote those flat characters thought he was doing a good job. But, as the reader, you could tell he wasn’t good at character creation.

Sometimes we don’t know what we don’t know.

If you want readers to connect with your characters, your characters must be convincing. They need to seem like real people even though they are figments of your imagination.

How do you turn your imaginary inventions into believable characters?

How do you bring those characters to life so that your readers fall in love with them and buy book after book?

Author and writing coach Becca Puglisi has helped thousands of authors create believable characters. She’s an international speaker, writing coach, and the bestselling author of The Emotion Thesaurus and other resources for writers.

Her books have sold 750,000 copies, and she is passionate about learning and sharing her knowledge with others through her blog, Writers Helping Writers, and her suite of online tools for writers called One Stop for Writers.

How do you create a believable character?

Thomas: What makes a character believable?

Becca: Many factors affect believability, but the most important one is that your characters need to mirror real people.

Your characters need to mirror real people.

Becca Puglisi

If you want your characters to mirror reality, you must base them on real human psychology. They need to function as real people. Their thought patterns and emotions should mirror those of real people. When you create characters with real human psychology in mind, they will look, sound, and act like real people.

Start by researching basic human psychology. I don’t have a degree in psychology, but anybody can get the basics and understand the baseline for how people act and react. Pursuing that learning curve will help you build realistic characters.

Thomas: You can research by listening to people talk. Listen with your ears and watch them as well. Notice their facial expression and think about how you’d describe it. This practice will ensure that your characters have real-life expressions and mannerisms.

Becca: Real-life interaction is super helpful. You know your friends’ sensitivities and triggers and recognize how they should act and respond.

When something happens that’s not quite normal, and maybe it’s over the top or understated, you can read their situation and recognize that something is off. Their physical cues are important.

Watching people respond to what’s happening is important. In real life, people aren’t always straightforward. There’s always subtext. When we’re talking, we don’t share everything. We are careful. But the body, especially the voice, reveals how people feel about what they’re saying.

When we apply that information to our characters, we can make them nuanced and deep.

What advice do you have for developing a backstory?

Thomas: We are a product of our experiences. Humans don’t emerge fully formed like Venus from the shell. And yet some fictional characters seem as if they started their existence on page one.

To remedy that problem, some authors write the character’s story before the story starts, so it feels as though the characters existed before the story began.

Becca: Backstory is crucial. When a story falls flat, it’s often because there’s a problem with the character. Most of the time, it’s because the author has not done all the work.

It’s important to know your character intimately. You must know who they were before the story started because when the story begins, your character will have a problem. They’ll be unfulfilled and dissatisfied, even if subconsciously.

Throughout your story, they’ll go on a journey to figure out what’s wrong and overcome what’s holding them back so they can achieve the goal that will fulfill them.

We, as authors, must know what past events formed the character because past events will impact the character’s responses and reactions to whatever you throw at them in the story.

Most importantly, the backstory helps you discover or determine your character’s emotional wound. Something happened in the past that was so traumatic or awful that it changed the character. That’s the emotional wound. It created a need to avoid that pain.

Backstory helps you discover or determine your character’s emotional wound.

Becca Puglisi

The emotional wound starts this domino effect of responses and actions that mirrors how people act in real life when horrible things have shaped them.

The emotional wound changes the character into someone different than they were, and often their flaws are a result of the wound. They have dysfunctions. They have adopted coping mechanisms in the wake of the emotional wound that they hope will protect them from experiencing it again.

The character’s flaws, dysfunctions, and coping mechanisms create problems for your character throughout the story and keep them from achieving their all-important, fulfilling goal.

Thomas: Here’s an example of backstory from history. As we record this, many people are asking why Russia is invading Ukraine. To understand the answer, you need to understand Russia’s emotional wound.

As a people and nation, their emotional wound was a guy named Genghis Kahn. He conquered Russia; and his descendants, the Mongols, raped and pillaged Russia for hundreds of years. It was terrible and humiliating.

Finally, a guy named Ivan pushed the Mongols out of Russia by being aggressive. He rescued the Russian people from the Mongols; and they all wanted to continue having a strong, aggressive king who could push the bad guys out and keep the people safe.

Once you understand that emotional wound, you can see why they’re so aggressive toward their neighbors. Even though Genghis Kahn is long dead, the emotional wound is still there.

It’s the same idea for people who fear dogs. Maybe a dog bit you when you were a kid, and now you’re afraid of other dogs even though those dogs didn’t bite you.

Becca: Wounding events are real and often horrible, but we often respond to them in illogical ways. We are so terrified that it will happen again that we look for ways to keep it from happening again.

One way to keep it from happening again is to assign blame. We want to know what caused it. If we know the cause, we believe we can take steps to prevent it.

A lot of trauma is not your fault. There’s nothing you could have done to stop it. But your brain wants to know how to keep it from happening again, so it fills in the gaps where the logic doesn’t make sense.

You’ll come up with illogical conclusions like “I was too gullible” or “I can’t be trusted” or “I’m not worthy of love.” Those are lies that stem from an emotional wound.

When a character starts believing a big lie about themselves, others, or the world, it changes everything. It changes their view of themselves and others and how they interact in the world.

Characters put up guards, which often become their character flaws.

For example, a driver who was carjacked after stopping to help a roadside “victim” may view their trusting nature as a flaw. It used to be a positive trait, but now it’s a weakness they need to eliminate. They replace it with being hyperalert and not taking people at their word.

We adopt coping mechanisms in the wake of our emotional wounds, and our characters will too. The results of the wound affect personal relationships, productivity at work and school, and many other areas of their lives.

Knowing that emotional wound will show you how your character will change. You’ll be able to see what’s holding them back, and you’ll know what you’re working toward in the second piece of the character arc.

In the first part of the story, we see what’s wrong with the character, but the character can’t see it. Your character may see their hyperalertness as a strength; but throughout the story, they’ll recognize it’s a response to what happened. Since it’s causing their problems, it needs to be changed and fixed.

The last part of the story will be about recognizing the problem and changing negative coping mechanisms to positive ones, so the character can respond in healthier ways that won’t limit them.

Then they’ll be able to move forward into health and growth and achieve their goal.

Thomas: We’re often unaware of our emotional wounds. That’s why we need counseling and therapists.

How do you authentically incorporate the character’s emotional wound?

Thomas: You don’t want to write, “As you know, Bob, you were hit by a car when you were six.” I can see a lot of bad ways to do this. So how do you do it?

Becca: I do a monthly first-page contest on our blog where people submit first pages, and I offer feedback.

One common mistake authors make is that they use the opening pages to explain what happened at the time of the emotional wound. But that is backstory and needs to be kept there.

The best way to reveal the emotional wound is to show it in the character’s actions, rather than explaining what happened to them in the past.

Every writer has heard, “Show, don’t tell.” Most of the time, telling interrupts the flow, slows the pace, and pulls the reader out of the story.

To show the emotional wound, you drop breadcrumbs. As your character goes through their story, you show them being triggered by something. You show an overblown response to something that wouldn’t bother most people.

Give hints in conversations they have. Perhaps someone’s name comes up, and your character turns the conversation. Those little hints are like puzzle pieces for readers. As they’re reading, they can see pieces of what happened, and they can put together the picture of the emotional wound.

Leaving breadcrumbs is effective because it doesn’t interrupt the story. The reader is firmly embedded in the story while learning about the character.

A flashback where the wounding event is told in its entirety is most effective at end of the story when the reader has already mostly figured it out.

If you’ve done the work of showing throughout the story, then the flashback isn’t always necessary.

Thomas: Flashbacks are tricky because they can kill the story tension if they’re not done right.

But they can also be powerful. In the movie It’s a Wonderful Life, George Bailey (protagonist) wants to go and see the world and do adventurous things, but his brother (antagonist) is holding him back. His brother keeps doing adventurous things instead, and George Bailey gets hurt because of it.

In this story, the emotional wound is also a physical wound. In one little scene, the brother runs off to do an exciting thing; and George Bailey has to rescue him. In the rescue, George’s ear is injured.

Potter wants what Bailey wants. He wants to give Bailey money to help him see the world. Bailey’s story is one of a man against himself. He heals from his emotional wound when he realizes that being a good husband, father, and community member is the true adventure.

It’s not that he got rid of the wound. He realized it wasn’t a wound in the first place.

Becca: That’s a key distinction. Most people don’t overcome their wounds. They don’t even recognize them. They just learn to minimize the damage.

Eventually, they learn to see the truth behind what happened and the lie they believe about themselves. When they replace the lie with truth, it sets them free.

That process allows them to recognize the wound and deal with it. It doesn’t mean it’s no longer traumatic or isn’t still a problem. That wouldn’t be realistic. But that process of replacing the lie with the truth allows them to minimize the damage and keep it from wrecking their lives so they can achieve their goals.

Thomas: The One Stop for Writers character creation tool forces authors to create characters who will change throughout the story.

If you create a character with an emotional wound that’s never addressed, your book will irritate readers.

Thomas Umstattd, JR.

You might get away with it for a few minor characters, but if you do that with all your characters and everyone ends up just as miserable as they were at the beginning, your reader will be unsatisfied.

Becca: In the past, it was much more common to have characters with flat arcs where there was no internal change. For example, Indiana Jones and the old James Bond don’t have an internal focus. The focus of their stories is achieving a goal.

I think people respond well on a subconscious level to the hero’s journey.

We see ourselves in the hero because we share common experiences and wounds. The hero’s journey also works for stories without a happy ending because even though the character ends up falling back on their old coping mechanisms, the process of recognizing the wound is the same.

Knowing your character’s backstory enables you to bring characters to life no matter where you want them to end up.

Thomas: Your character’s response to their emotional wound determines whether their story is tragic or not.

You can use the same techniques to make your villains more believable.

Gollum is a compelling villain because he has such a clear emotional wound.

His one source of happiness is the ring, and that’s the lie that he believes. The truth is that the ring is poison, and it’s corrupting him. His emotional wound was killing and taking the ring when he was young. Throughout the whole story, he’s trying to get the ring back.

When he finally gets it back, it kills him. He falls into the fire and dies trying to save the ring he loves so much. He’s given over to his sin, and readers see the consequence of that.

The tragic end of Gollum is much more powerful than if he had been redeemed.

Becca: We don’t give villains enough credit. For a while, the trend was to make villains extremely powerful, evil, and scary. They didn’t necessarily need a story.

Compelling villains have a reason for their villainy. When readers understand the reason for the villain’s behavior, they start to feel for them a tiny bit.

They’re not necessarily rooting for the villain; but they develop a bit of empathy, which is good because it creates some conflict for the reader. They recognize the villain is a bad person and don’t want the bad guy to win, but they’re conflicted because they empathize with the emotional wound to an extent.

Backstory is important if you’re writing a romance because your main character and your love interest will have goals and obstacles that keep them from achieving what they want. You have to know the setup and backstory for each person.

Thomas: One great example of a villain with a backstory is Marvel’s Thanos. He was on an overcrowded planet that consumed its resources, and everyone died. His wound was seeing his loved ones and his planet die.

If only someone had had the will to kill the surplus population, the planet would’ve continued to thrive and be happy.

Thanos believes the lie that he needs to be strong enough to kill the surplus population so that good can flourish. That’s his worldview.

In the movie Endgame, he’s actually the protagonist. He moves the plot forward. The Avengers are the antagonists trying to stop Thanos from doing the evil he wants. The writers flipped the script completely, and Thanos becomes a compelling villain because you understand his emotional wound.

How do you find the right words to convey your character’s emotions?

Thomas: Conveying the emotional wound makes the story resonate, but how do we find the right words to convey the emotions?

Becca: At One Stop for Writers, we have The Emotional Wound Thesaurus, which highlights over 100 traumatic events and how you can use them in your story. It provides basic research for figuring out what might have happened to your character.

Emotions drive a story. If we can adequately convey the character’s emotions, we can tap into the reader’s emotions better.

When readers see a character struggling through difficulty and the emotions are conveyed effectively, the reader gets an emotional echo because they have felt the same or been in a similar situation. That connection creates an empathy bond that makes the reader want to continue reading to make sure that the character will be okay.

What is The Emotion Thesaurus?

The Emotion Thesaurus has over 130 different emotions your character could experience, and it provides ideas about how you can show those emotions in your writing.

We all realize that telling emotions instead of showing them is a universal problem every author must address.

I might discover my character is always clenching his fists, shuffling his feet, or shrugging his shoulders; and I can’t find another way to show what that emotion looks like.

Angela Ackerman and I wrote it because we needed it in our own writing. It has physical cues your character might exhibit when feeling emotion or thinking through something.

It talks about the visceral, internal responses, which other characters can’t see. But you, as the author, can share those visceral responses when you’re using a first-person viewpoint character. You can show what’s happening inside.

Everybody has experienced the stomach dropping, butterflies fluttering, or heartbeat racing. We all know exactly what the character feels when we see those responses.

The Emotion Thesaurus is a brainstorming tool.

If you know your character will be feeling angry in a scene, you might need ideas about how to show it instead of saying, “Joe was angry.”

The Emotion Thesaurus gives us options for conveying that emotion, but mostly it’s a jumping-off point. Reading through the possibilities is one way to get your gears turning. In fiction, the best emotional demonstration is tailored to the character’s personality and backstory.

You know their emotional baseline and how they typically respond. When you consider their circumstances alongside their personality and backstory, you can tailor a response that makes sense for that character.

The more you customize their response, the more believable your character will be.

What encouragement do you have for an author trying to create characters who are different from each other and different from the author?

Becca:

- Start looking at people you know.

- Pull from real life.

- Consider combinations of different character traits and different characters together.

A lot of the sameness happens because we have the same people in the same situations we’ve always seen. Maybe you change their education level or their wound. Things will change if you can remove or change one factor and replace it with another.

Thomas: We do the same thing when we’re cooking the same meals, and everyone is tired of the same food. If you need new ideas, you leaf through a cookbook. You may not make any of the recipes, but reading the cookbook will remind you of something you used to make. Suddenly, there’s variety in your menu.

You can bring new life to your story in the same way. I read a series where the author could have used The Emotion Thesaurus. It was a military book, so I wasn’t looking for much emotional resonance; but I was looking for some. As I read, I noticed every character was “grim” or “gazing grimly over the battlefield.” The good guys and the bad guys were grim, and I started to wish there was another word he could have used.

The Emotion Thesaurus could have expanded his vocabulary and helped him draw out the characters.

Becca: It’s a universal problem for authors. When Angela and I started critiquing each other’s work, we saw that our characters were doing the same thing over and over.

We started making lists of emotions with different things that could be happening so that we would have more options. When we started Writers Helping Writers, we blogged about one emotion per week.

You’re not pulling phrases out of The Emotion Thesaurus and plunking them into your story because that won’t always make sense for your character. But you can use it to discover new ways to breathe life into your character’s emotional responses.

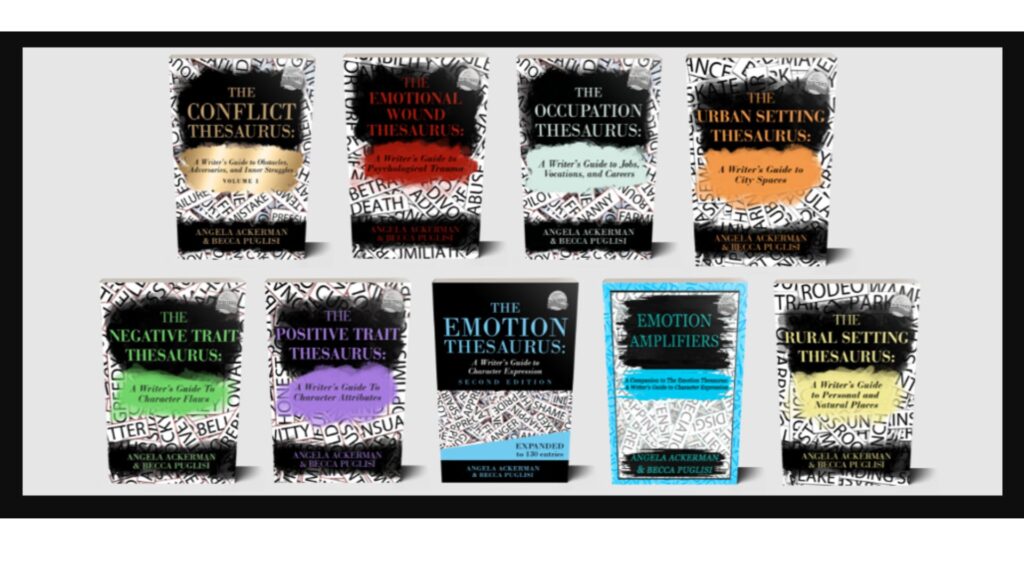

We have nine books in our series that cover different writing topics.

Will using The Emotion Thesaurus make my writing sound like everyone else’s?

Thomas: I have a book of the best headlines ever written.

I find it helpful to look through that book when I’m trying to come up with a good title for a blog post or podcast. I haven’t used any of the actual headlines, but seeing the different headlines gets my gears turning.

I end up creating something new and useful.

The Emotion Thesaurus isn’t meant to make someone write like you. It’s meant to get your creative juices going. A bit of diversity in our reading and thinking can get us out of that rut, and suddenly we’re on a new path to better writing.

Becca: One good exercise is to make notes when reading passages that show emotional responses well. When authors convey emotion in a way you had never thought about, make a note of it. I keep a spiral notebook by my bed, and if something jumps out at me while I’m reading, I jot down the phrase.

When I get stuck in my writing and can’t figure out how to convey the emotion, I return to my notebook to see what other successful authors have done. I deconstruct it and discover how they said it differently.

That has helped me learn to show emotion, describe settings, and show the physical characteristics of my characters. There are many other ways to show the reader “Her hair was brown, and her eyes were blue.”

Thomas: We do something similar when we go out to eat and order a new dish. You think, “I could make something like this.”

Once I realized that Thai food often includes peanuts, I tried putting peanut butter in my stir-fry.

It was incredible, and I liked it. If I hadn’t tried other Thai food, I would’ve never thought to use peanut butter in stir-fry.

As you study craft, you start to read books differently. You see how the pieces fit together. You notice the decisions the author made. In the process, your fiction reading becomes craft reading. You read books looking for the protagonist and his emotional wound. You gain a vocabulary for understanding what’s happening, and that inspires your writing.

Becca: As readers, we can see when something is good or bad. But it’s not until you start digging in that you can identify why it was bad or what should have been done differently.

When Angela and I started writing, we decided to take a year off and read a bunch of craft books. We read them separately but at the same time, and then we discussed them. That year, our knowledge exploded. The learning curve shortened dramatically because we were intentional about it.

We read:

When you’re exploring craft with someone else, you have accountability. You’re able to bounce ideas and verify observations you couldn’t articulate. It was an exciting year, and it jump-started our writing.

- Writing Screenplays That Sell by Michael Hague

- Story by Robert McKee

- Self-Editing for Fiction Writers by Renni Browne and Dave King

- and many others.

Thomas: During the first year of our course The Five-Year Plan to Becoming a Bestselling Author, students read a craft book every month and then write a short story to implement what they learned. The first year is often revolutionary. Authors need to read books on structure, creating characters, and dialogue. Craft books will transform your writing.

What other resources do you have for writers?

Becca: After The Emotion Thesaurus took off, we brainstormed other areas of writing we needed help with. We figured that if we needed help, other writers might too.

Characterization was a big piece, so we wrote a set of ebooks on positive and negative traits. We discuss where those traits come from and how you can show your character’s personality through their actions, responses, and speech.

We also wrote books about rural and urban settings that explore a place through the five senses. We discuss the importance of showing the setting and everything it can do for your story and character. It can provide mood, foreshadowing, characterization, and many different things.

We have a book on occupations to explore characters’ jobs, how they contribute to the story, and why characters might choose certain occupations.

Our latest book was on conflict. We cover how conflict plays into the character arc. Conflict creates a need to make choices that have consequences. That’s how you get your character moving toward a certain decision or change that has to be made.

We’re publishing a second conflict volume in the fall of 2022.

We call each volume a “show don’t tell database.” They all deal with different aspects of showing instead of telling. We believe that’s key to pulling readers in and taking your writing to the next level.

Does an online subscription to One Stop for Writers give you access to all those books?

Becca: Our blog, Writers Helping Writers, is where you can find information about our books with purchase links. It also has lots of information on different writing topics.

One Stop for Writers is a subscription-based website that takes the content from our thesauruses plus seven additional unpublished thesauruses and compiles it into a searchable database online.

We also created tools on the website that use the content from the books.

We have a character builder that pulls directly from emotional wounds and positive traits thesaurus and combines that information to help you build a character.

We have a story structure tool that helps you map your story using Michael Hauge’s six-step story structure.

We have mapping and timeline tools and an idea generator if you need a kickstart. We just created a storyteller’s roadmap that takes writers through the process of turning an idea into a story.

Writers Helping Writers is the informational piece of our puzzle, and One Stop for Writers helps you apply the information in a practical way. We’re constantly adding new resources and new tools.

Thomas: Authors can always get started by buying The Emotion Thesaurus on Amazon or check out our course The Five-Year Plan to Becoming a Bestselling Author. Patrons of the Christian Publishing Show save 50%.